Blacksmithing Through the Ages: An Era of Innovation

(Image credit: Historyflame)

Our third foray into the examination of blacksmithing through the ages brings us to the Late Iron age (If you haven’t yet read our previous articles in this series discussing the Bronze Age and Early Iron Age, be sure to check them out). The Late Iron Age was a period defined by advancements in technique and technology, during which the knowledge gained by these blacksmiths would pave the way for modernized militaries and economies worldwide.

It is difficult to define the time frame of the Iron Age on a global scale because all societies experienced this period locally, within their own civilizations. Because of this, some Iron Age periods lasted longer than others, with historians typically considering the last to be Germanic Iron Age, which ended approximately around 800 AD.

The Late Iron Age began roughly around 500 BC when iron had almost entirely replaced bronze as the preferred metal of the blacksmith. Nearly all equipment, weapons, and tools were made from iron. As the Early Iron Age progressed into the Late Iron Age, blacksmiths continued to learn and improve upon their knowledge, with the later stages of the Iron Age bringing several significant innovations.

“ Steel was stronger than wrought iron and better at holding an edge.”

Perhaps the most critical advancement of the Late Iron Age was the capability to produce steel. Steel was stronger than wrought iron and better at holding an edge. Although still not high quality, some civilizations could regularly make steel weaponry by the Late Iron Age.

(Image credit: Blade Smith Forum)

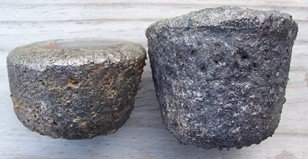

Early steel was produced in crucibles and was known as crucible steel. In this method of steel making, the blacksmith melted iron and pig iron (iron with very high carbon content) together with a flux. Flux is a substance that can be used to increase fluidity during the smelting process, such as sand, glass, and ash. The high carbon content of the pig iron gave it a lower melting point allowing it to turn to steel slowly. Crucible steel was primarily a product of Asia, namely India and Sri Lanka, around 300 BC. Their steel, known as Wootz (later Damascus), was heavily traded throughout the continent. Blades forged from Wootz were highly regarded for their strength, durability, and decorative patterns.

RELATED: FORGE WELDING TECHNIQUES EXPLAINED: DAMASCUS

By 300 BC, the Roman Empire had gotten into the game producing their own steel weapons. Besides importing steel from other countries, they mined iron from Noricum, a Celtic region near modern day Austria and Slovenia. Steel produced from this iron was known as Noric steel, and the weapons forged from it became the primary choice of arms for the Roman military following Noricum’s annexation into the Empire in 16 BC.

(Image credit: Wayfare History Network)

The talented Roman blacksmiths were able to produce steel in structures called “bloomeries”. While the bloomery heated the iron enough to change the outside to steel, the core remained iron. The Roman gladius is perhaps the most well-known steel weapon of the late iron age. It was made of several layers of steel rather than just a single piece. While Roman steel was good enough for weaponry, they continued to use iron for nearly all other aspects of their lives.

Another significant advancement coming out of the Late Iron Age was the quenching process. Quenching is a heat treating process during which smiths heat a blade up to a certain temperature before rapidly cooling it using a quench medium (typically oil or water, among others). This process changes crystalline structure of the steel resulting in a harder, more durable blade. Although not widely used until the 15th century, there is evidence that blacksmiths in various regions were experimenting with quenching to solidify metal by the end of the iron age. For example, historians have found evidence of Chinese bladesmiths quenching steel swords as far back as 400 BC.

“Late Iron Age blacksmiths were producing ironworks, including amour, chariots, hammers, axes, chisels, ploughs, and many other products that made everyday life a little easier.”

Steel production and the quenching process advanced weaponry significantly during the late Iron Age, but neither was widely used. Iron remained the primary choice of blacksmithing during this time, and blacksmiths’ growing skills with iron allowed them to experiment with sword creation. During this time, swords in the Northern regions of Europe became longer and lost their curved edges.

Late Iron Age blacksmiths were producing ironworks, including amour, chariots, hammers, axes, chisels, ploughs, and many other products that made everyday life a little easier. Aside from this, though, the late Iron Age is responsible for one major object that many often overlook; coins.

“As coins slowly became a form of currency, their demand increased and eventually became a staple of human civilization.”

The first coins, Lydian Lions, were produced around 600 BC and were the basis for which Greek, then Roman, coinage was based. Coins were made of gold, silver, copper, bronze, and iron. Creating coins was simple enough; heat the metal and hit it over an anvil or hard surface. Some coins were even cast, depending on the metal type. As coins slowly became a form of currency, their demand increased and eventually became a staple of human civilization.

(Image credit: Glevalex)

The innovations in iron technology are the capstone of the Iron Age. Blacksmiths learned the secrets of iron working and later were able to create steel on a small scale. Their ongoing work with iron led to better weaponry and tools. As time progressed, blacksmiths became essential figures in every town. They were the hardware store and mechanics of their towns and created everything from nails to swords.

Be sure to check out the first two articles in our special series “Blacksmithing through the Ages” in which we discuss the Bronze Age and the Early Iron Age. Want more bladesmithing content? Be sure to follow us on Facebook and Twitter and you’ll never miss a thing.

About the Author

More from Amanda